Steve’s Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Story

Steve B., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptom: Low white blood cell count

Treatments: 7+3 chemotherapy, pre-transplant conditioning, stem cell transplant

Steve’s Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Story

A year away from retirement, Steve was looking forward to his final year as a Sociology teacher until a routine check-up revealed an alarmingly low white blood cell count.

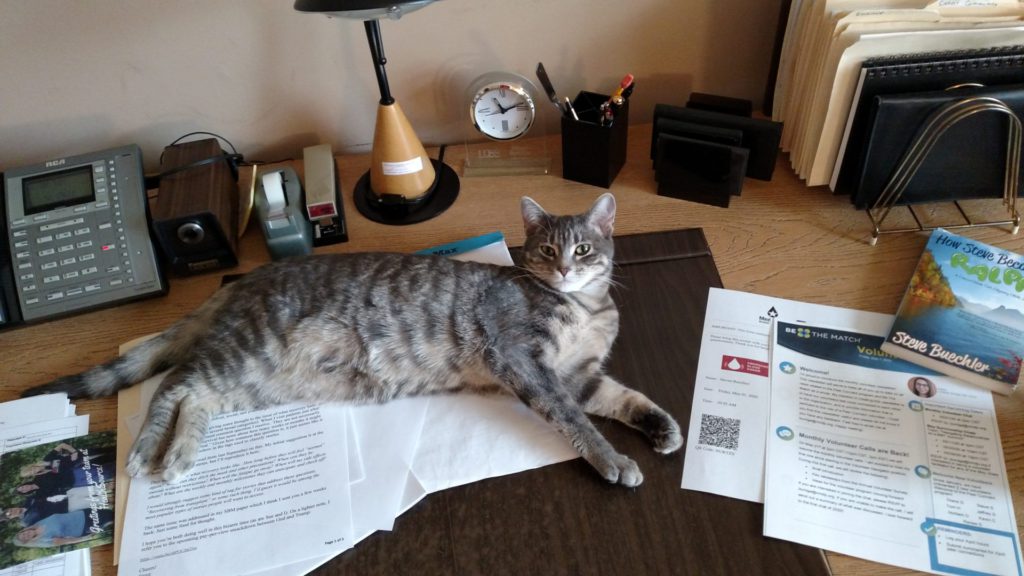

Today, Steve is a poker player, traveler, ambassador of sociology, and going on 5+ years as a volunteer in the cancer community. He also wrote a book about his experience called, “How Steve Became Ralph: A Cancer/Stem Cell Odyssey (with Jokes).”

Steve shares his story about being diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), receiving a cord blood stem cell transplant, and how mindfulness meditation yoga helped him stay positive throughout his journey.

- Name: Steve B.

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Staging: N/A

- Symptoms:

- Low white blood cell count

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy

- 7+3 Cytarabine & idarubicin

- Pre-transplant conditioning

- Cytoxan

- Fludarabine,

- Total body irradiation

- Stem cell transplant

- Cord blood donor

- Chemotherapy

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Diagnosis

- Hospital Stay

- Chemotherapy

- Starting chemotherapy

- What were the effects of 7+3 chemotherapy?

- Collaborating with doctors to find the best treatment

- How did you take precautions to avoid infection?

- How did you occupy your time during your hospital stay?

- Did anything help you cope with your diagnosis?

- Being treated like a person rather than a patient

- What was it like being without your wife during your hospital stay?

- What was returning home like?

- Stem Cell Transplant

- Life After Cancer

- Reflections

- Turning gratitude into giving back

- The importance of trusting your medical team

- What led you to write your memoir?

- The power of mindfulness and meditation

- Connecting with people through humor

- Do you think positive thinking led to your outcome?

- Discovering a common core humanity in everyone

- The value of caregivers

- What advice would you give to other cancer patients?

Diagnosis

Tell us about yourself

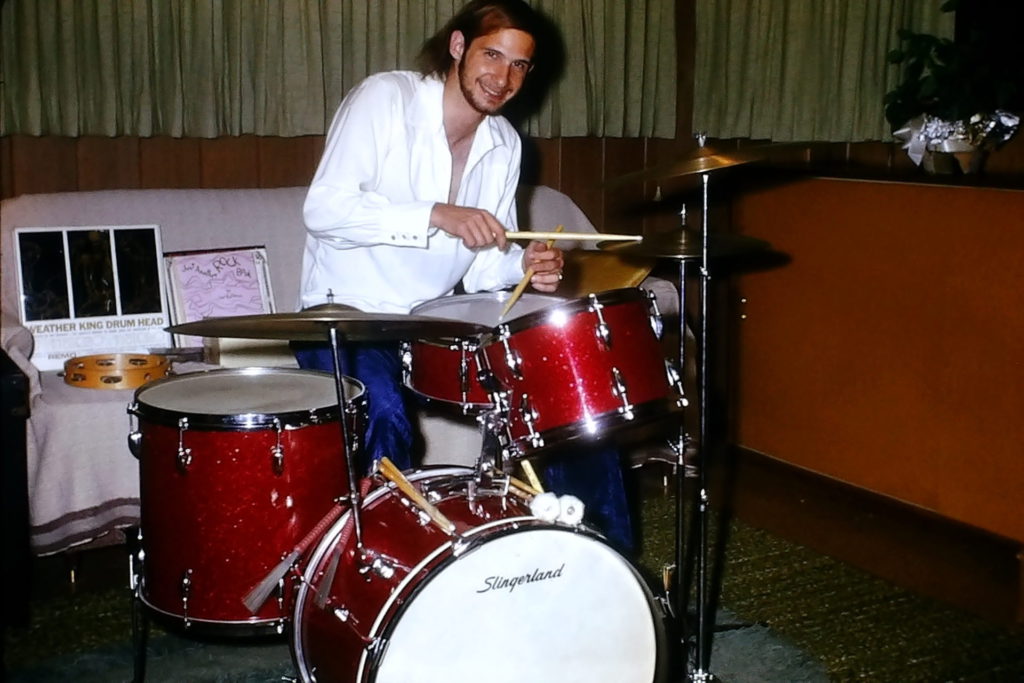

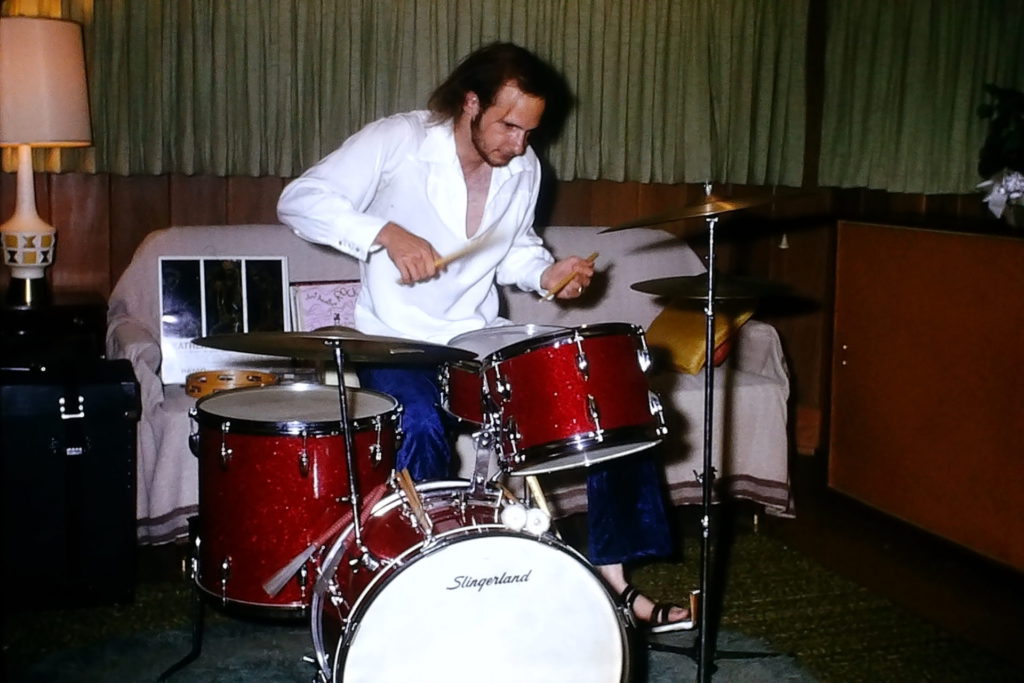

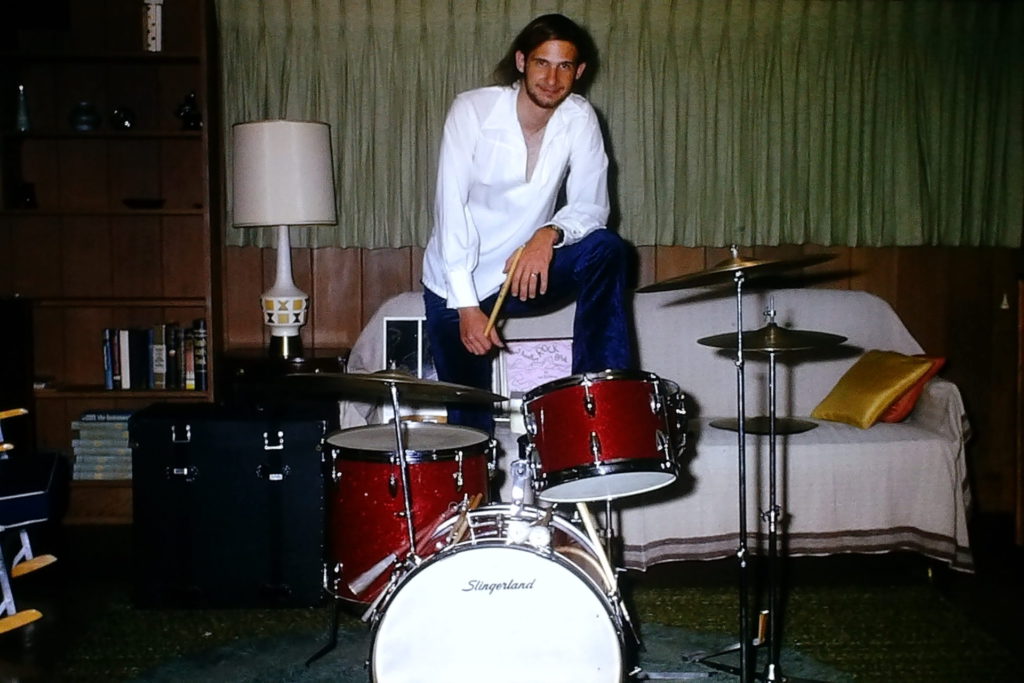

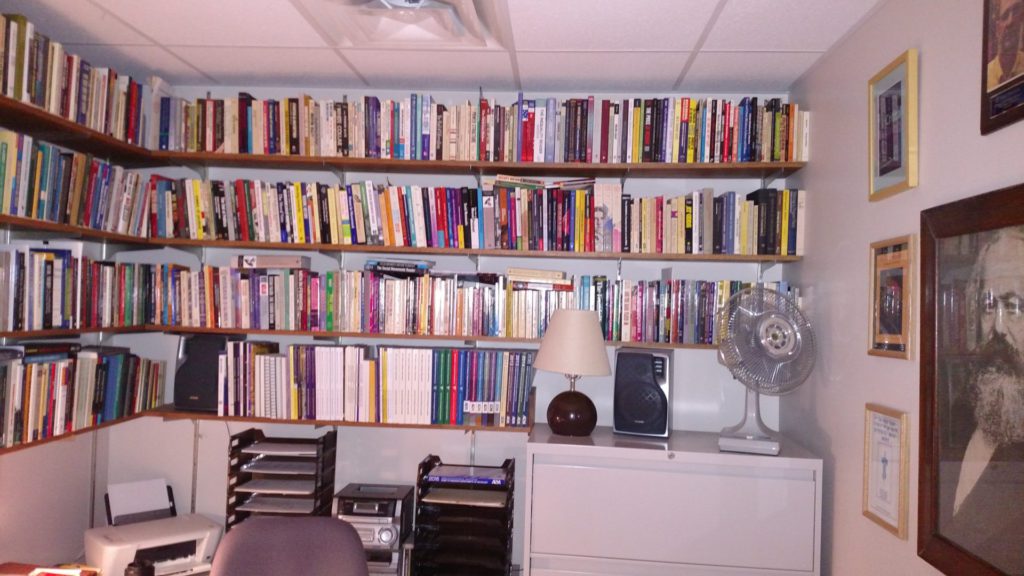

I need to start with my occupation and my profession, which I dearly loved because I spent about 40 years as a practicing sociologist. And although I’ve retired, I continue to be in love with my discipline because it’s a window into the world in so many different ways.

I used to urge my students – unless you plan to live on a desert island for the rest of your life, you really need to take sociology to understand the world that’s going to shape you. So you can be an active agent in that world and know how to respond and react.

We can look big picture of the world capitalist system, or we can micro-focus on 2 people interacting and everything in between. I find it to be a completely captivating perspective for looking at the world. I’m quite the ambassador for trying to recruit people into sociology when I’m not playing sociologist.

I’ve been to Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness for more than 30 trips, usually a week-long, sometimes 10 days, in the wilderness where you pack everything that you’re going to need and try to survive for 10 days in a remote wilderness area. It’s a great retreat from everything having to do with the modern technological world that we live in.

I like to play poker on the side and shoot pool with a buddy of mine. My wife and I have done a number of cruises, including the Mediterranean many times. I have interests outside of being a sociologist but that’s been my core identity for most of my adult life.

How would you summarize your cancer story?

It would underscore the suddenness with which this came over me. The only time I was in a hospital before my treatment for AML was on the day I was born in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1951. I had the honor of being the 200,000th officially registered patient at Madison General Hospital, so I was destined for something, but I hadn’t been in a hospital other than to visit people for 64 years.

I landed in a hospital very quickly and I stayed for a very long time. It was all new to me. If you would ask me to define leukemia, I couldn’t have done it. I knew nothing about it, I had no exposure to it, and I had no reason to have any familiarity with it. It was a real crash course in trying to figure out what the heck was going on and where was it going to go.

I’d give a nod to the value I found in writing my story, that was one of my basic survival mechanisms. Maybe because I’m an academic and I’m comfortable with writing, but it was more than that. Telling my story for myself and for others was a way of maintaining my sanity.

A routine check-up reveals an abnormally low white blood cell count

I kept the appointment at the last minute. Arguably, it may well have saved my life because they did some routine lab work and came back with very low white blood cell counts which was a red flag for my doctor.

It was the spring of 2016. Professionally, I was looking forward to one more year of teaching and then I was going to glide into a carefree retirement. But I had an annual physical schedule, which they always encourage us to do – go in and get your checkup.

Things were going so well, I almost canceled it. I thought, there’s nothing to learn here. I feel fine. I’m doing well. Why do I want to spend an afternoon going and doing this? But I kept the appointment at the last minute. Arguably, it may well have saved my life because they did some routine lab work and came back with very low white blood cell counts which was a red flag for my doctor.

He said, “I think you should go see a hematologist.” I didn’t know what a hematologist was, but they made an appointment. It was an office of Hematology/Oncology. I thought, what tree are these people barking up? I feel perfectly fine. Oncology is the furthest thing from whatever’s going on here.

Receiving a diagnosis

…he said in about a 10-minute conversation that I had acute myeloid leukemia (AML). I didn’t know what that was. I have 50% blasts in my bloodstream. I didn’t know what that was.

To humor my doctors, I met with this hematologist. They were also very concerned and said, “The next step should be getting a bone marrow biopsy to see if we can rule in or rule out what may be going on here.” I said, “If that’s what you think is appropriate, I’ll follow your recommendation. But I have no symptoms. I’m sure when we do this thing, it’s going to rule out whatever you think is going on that’s so bad.”

Call it confidence, call it naive, call it stupid, but there I am going in. It was a heck of a week. The biopsy was on a Monday afternoon. On Tuesday, I swam my normal 50 laps, saw a chiropractor, did some shopping, and I ate dinner out. Nothing could be more normal.

Wednesday morning, I played a weekly poker game with some retired guys and that afternoon I came home and my wife said, “That doctor called and wants you to call him back.” I placed the call thinking, again with this overconfidence, this is when they’re going to tell me everything is really fine.

Instead, he said in about a 10-minute conversation that I had acute myeloid leukemia (AML). I didn’t know what that was. I have 50% blasts in my bloodstream. I didn’t know what that was.

He said, “It’s imperative that you get to a hospital immediately. We’ve made an appointment for you at 9 a.m. tomorrow morning. Report to this hospital,” which happened to be across the metro from the west side of the Twin Cities where I live to the flagship hospital for my insurance.

The rest of that day is a blur. I can’t clearly remember it. I wasn’t scared or frightened or panicked. I didn’t have any conception of what was happening and how I should feel. Numbness prevailed through that evening.

I packed up some things, not knowing what to pack. They said I could expect a long hospital stay. The next morning, my wife and I drove across the metro.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

How did your wife react to your diagnosis?

Like me, she had no idea how to react and what this meant.

What was it like not knowing much about your diagnosis?

It’s the “Fast and Furious’”of blood cancers. It’s the deadliest of the blood cancers. I’ve heard people say, without treatment upon diagnosis, life expectancy can be measured in weeks or months if you’re lucky. It’s that fast.

My first reaction was not to go on Google and look this stuff up. Intuitively, I knew that was not a wise thing to do. In fact, throughout my early treatment, I remained naive about what this disease was and what course of treatment I could expect. In an odd way, I think that served me well until I needed to hear the hard story about what this is and make some decisions.

I was glad I didn’t know much going in because I think it would have been overwhelming. There is some research that’s been done specifically on AML patients that finds, the more they know about their prognosis, the more stress they feel and the more physical symptoms they experience. Depression sets in.

It’s not a pretty story. It’s the “Fast and Furious” of blood cancers. It’s the deadliest of the blood cancers. I’ve heard people say, without treatment upon diagnosis, life expectancy can be measured in weeks or months if you’re lucky. It’s that fast. Not learning all of those facts about AML until I needed to know them to make decisions about treatment, served me well.

Hospital Stay

Did the doctors tell you how long you’d be at the hospital?

They said weeks, but they didn’t specify much more than that.

Once I got my feet under me, I wanted to be a proactive patient and know everything from a scientific perspective. How does this disease work? How does my treatment work? I wasn’t curious about the prognosis. It was that division of labor – I want to know these things but not that thing.

Transferring to a local hospital

We drove across town, we arrived at the hospital, and we spoke with a very good oncologist. What I appreciated is he got to know us as people and not just as a potential patient.

At one point he said, “I think we could take good care of you here, but you probably want to be treated closer to home because of all the back and forth that’s going to be going on for you and all the people visiting you. I know someone across the Twin Cities, an oncologist. I can give her a call and see if she might be able to take you on as a patient.”

It took a couple of hours, but the connection was made so we drove back to a hospital much closer to town and checked in. There were some delays here and there, but that’s pretty typical in hospital admission.

Watching the medical workers was reassuring

They said I would be going to room 4-East-3. I envisioned I was going to be in someplace called room 4, in bed 3 in a barracks-style room, like an old war movie. That’s how little I knew about hospitals. It turned out I had my own room. It was fourth floor, room 3 in a very interesting hospital space where there was a central nurse’s station and about a dozen patient rooms in an oval shape around that nurses station.

I ended up liking that because I was a person that wanted to keep my door open. I wanted to see what was going on. I wanted to hear the chatter. I wanted to be connected to something larger than just my hospital room.

The more I thought about it, I realized being able to watch the nurses and the doctors go about their business in a perfectly normal way, as if this was a routine day at the office for them…I don’t know what’s happening to me. I don’t know what’s going to happen to me, but as I watch these people go about what they’re doing, they seem to know what they’re doing. I can tell they’ve done this before. I feel like I’m in good hands. It was really reassuring just to have that connection from the very first day.

I wanted to see what was going on. I wanted to hear the chatter. I wanted to be connected to something larger than just my hospital room.

Describe how your wife ended up in the hospital while you were there

I ended up in this hospital on Thursday afternoon.

Another side story that I should share because it was pretty impactful – my wife wanted to stay in my room that night to keep me company. I said, “There’s no good place here to sleep. You might as well go home.”

She got up out of one of those huge recliners that they have in hospital rooms and her right leg buckled under her and she winced in pain. We didn’t know what was going on. She limped out of the room and off she went.

The next morning, I get a call that she can’t get out of bed, the pain is so bad. She calls her sister, her sister comes over, they call 911, and they send an ambulance. An hour later, she arrives at my hospital in an ambulance at the ER.

It turns out she has a hairline fracture in her femur bone and she’s going to need surgery so she checks into my hospital and gets a room 2 floors above me. She stays there for a week. During that same week, I start my chemotherapy treatment. I checked into the hospital on Thursday, Sue checked in on Friday night.

Chemotherapy

Starting chemotherapy

I started chemotherapy, it was called 7+3. It was the standard of care at the time. A week-long infusion of cytarabine and another medication called idarubicin.

I don’t think I saw my oncologist until Saturday after I started chemo. That was when she began to lay out what was going to happen in the short term. She said, “You can expect to be here for at least a month. Because this chemotherapy is going to create a lot of side effects, you’re going to get really sick. You’re going to have infections and fevers. We know how to treat them, but they’re serious enough that we’re not going to let you leave here until you get through that process.”

From the first day or 2 that I was there, I had a short-term sense of what was going on. They were vague discussions after that. “You’re going to need more treatment, but we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.” They really wanted me to focus on this first round of treatment because the goal is really just to stop the leukemia. Ideally to get into remission, and that’s going to buy you enough time to then consider what are my options. What comes next?

What were the effects of 7+3 chemotherapy?

I’m glad I didn’t know this at the time, but they say the chemo I had was really harsh, really brutal, and really wicked. It was nasty. They didn’t tell me that at the time. They said this is the treatment, and I said, okay, let’s do it.

My oncologist said about day 10, these things will begin to happen. I got to day 10, I’m doing fine and I’m cocky. The next day, everything just hit the fan. Colitis, E. coli infection, full body rash, headaches, fevers, diarrhea. You name it, I had it. She was exactly right, she was just off by 1 day. For about 2 and a half weeks it was awful.

Collaborating with doctors to find the best treatment

I gained a real appreciation for infectious disease doctors. These people would come in every day and say, “What are your symptoms today?” I’d rattle them off and they’d say, “This antibiotic, we can get one that’s a broader spectrum. We don’t know exactly what’s going on. Let’s switch it out for this one.” Same with the antivirals, the antifungals.

At a couple of points, it was more like a collaboration because they couldn’t figure out exactly what was causing the side effect. I remember one day saying, “I’ve been on that antifungal medication from the very first day, and somehow I think that’s complicit in some of these side effects.” And they said, “Okay, we’ll switch it out with something else.” That problem got a little better, so it was nice to see I could have a voice, I could have some input, and that on some questions, they just don’t know.

There are so many different symptoms going on that could be many different things, and people react differently to drugs. I felt like it was an experiment in itself to find what medications and what combinations would do the best to get some of these symptoms under control.

How did you take precautions to avoid infection?

They gave me medicated body wipes I’d have to use several times a day. Any possible source of the infection, I had to control it. Wearing masks long before they became fashionable with COVID, hand washing – they urge that completely. If I ever left my room without my mask, they dressed me down and said, “You can walk the halls, but you got to have that mask on.”

I learned a lot about controlling infectious diseases. Not that it prevented most of the things that got me. I also learned some of the things that got me had been living in my body my entire life. They said that’s probably true for the E. coli bacteria. After the transplant, I had a flare-up of the cytomegalovirus. They said that’s probably been in your body your entire life. If you have a functioning immune system, all that stuff is kept under control. But without it, they run rampant.

I had several visitors. They always had to be masked and keep some distance. It was a fairly spacious hospital room and they didn’t stay for a long time so that was quite manageable.

How did you occupy your time during your hospital stay?

What I appreciated the most is throughout this period I was able to leave my room and walk the halls with a mask. Later at my transplant hospital, it was more confined to quarters for 2 and a half to 3 weeks. But at my initial hospital, the first week when I was receiving chemo, I could leave my room with the chemo on an IV pole, but only walk through the cancer ward on the fourth floor and no further in case there was a spill. They knew how to deal with it, but the rest of the hospital, not so much.

To be seen, recognized, and acknowledged as a full-fledged ambulatory person and not just a sick patient in a bed really meant a lot.

Once I was done with the chemo, I explored every nook and cranny of that hospital. I was on different floors. I walked it from one end to the other. I walked out the front door to put utility bills in the mailbox up by the road. Walking was one of my basic survival strategies. It felt so good to get up and move and to see other people.

After a couple of weeks, the nurses said, “We’ve been watching you and we think you’re walking about 5 miles a day, 3 separate times per day.” That just became my routine. The best part of it was, as I walked past different staff and nurses in different parts of the hospital, they’d recognize me and I’d recognize them. We’d wave, chat, and smile and we’d share a couple of stories.

To be seen, recognized, and acknowledged as a full-fledged ambulatory person and not just a sick patient in a bed really meant a lot. I’ve told nurses that I hope they appreciate that something as simple as a smile or a wave or just some acknowledgment of recognition can mean a whole lot to a patient when they’re vulnerable.

Did anything help you cope with your diagnosis?

Right at the top of the list would be the combination of practicing mindfulness meditation and yoga. The really serendipitous thing is about 2 months before my diagnosis, I received a flyer promoting a community education class on these topics. I thought, I’ve dabbled around with meditation and yoga and I’ve never done it seriously. I’m not very good at it, but I’m going to take this class. It was a time in my life when I really needed to incorporate that into my daily activity.

About 8 weeks before my diagnosis, not knowing it was coming, I was meditating, I was doing yoga. One of the gurus of this approach, Jon Kabat-Zinn, has said we can change the way our brains are wired in as little as 8 weeks of systematic practice. It was about 8 weeks before my diagnosis hit.

For most of my life, I could be mistaken for a chronically anxious, anal-retentive, obsessive-compulsive control freak. You would think cancer would throw me through the roof and it was almost the opposite.

I know a lot about staying in the moment, rhythmic breathing, staying in touch with my body, yoga, and the body scan. From the very first night in the hospital when things finally quieted down and Sue left and the lights go out, it was like, if the demons are ever going to come it’s at night. I did a body scan and I started with my toes, my ankles, and my feet. By the time I got to my torso, 15 minutes later, I fell asleep.

I did that every night in the hospital and I never lost any sleep to anxiety. The nurses came in at all hours and people came in for medication checks and vital signs, so you can’t sleep in a hospital anyway. But it was never from fear or anxiety because I had this powerful tool to deal with it.

Being treated like a person rather than a patient

I was deliberately a proactive patient. I sought out those relationships with nurses and when you’re there for 37 days, you have a chance to do that. They got to know me as a real person, and that was tremendously important for all the reasons we’ve just discussed.

Every couple of days I’d be sent down to imaging for an x-ray or a CT scan and an orderly would show up at my door with a wheelchair ready to take me to imaging. I would say, “I’m walking 5 miles a day in the hospital. I know where imaging is just as well as you, so I’m going to walk.” Sometimes they would say, okay. Other times they would force me to get in a wheelchair. I really resented that because I was being treated as a generic patient and not the individual that I am.

When I got to the imaging, [it was] kind of the same thing with the techs. I’m the 93rd person they’re doing today so they treat me very generically. It was very alienating till I got back to my room and my familiar nurses. It was like, okay, now this is home. You’re my people. We’re back on track.

What was it like being without your wife during your hospital stay?

She was in the hospital with me for the first week, but then she went to a transitional care unit (TCU) for a month of rehab. We learned how to do FaceTime and various kinds of screen-sharing things, but it was very weird and very artificial. No one looks good on a little tiny phone screen. Some of the communication was kind of minimal, but we both had our own struggles to bear.

She has a sister who lived in town, and she was a crucial go-between. She would take things back and forth, bring the mail to me, and the newspapers to her. Having someone like that is a lifeline to keep our lives connected. That helped a lot.

What was returning home like?

It was a whole month after [Sue] left for her TCU and I went through my remaining month of hospitalization. After 5 and a half weeks, she came home 1 day before I did. Our home had been unoccupied for roughly 5 weeks. Open the refrigerator and it was like a petri dish, so we had to clean that out.

Gradually we got back to a little bit of normality as I had to figure out what’s the next stage of treatment and where is this eventually going to go. She still had a fairly long recovery, but at least she could be home and maneuver a lot of the time. We shook our heads like no one was going to believe this happened to us.

At the same time, there was that little storm that hit about 3 weeks into my hospital stay. That was an interesting thing to learn from my neighbors. One night they emailed me photos of 2 60-foot trees that fell down on our house while it was unoccupied. I was dealing with a tree service, contractors, and roofers remotely, trying to get the trees out of there and the house repaired. That all took care of itself.

In my family, there was an old saying that bad things happen in threes – my cancer, Sue’s broken leg, trees falling on the house. It should be clear sailing from here out. Not exactly, but it helped to think that way.

Stem Cell Transplant

Deciding the next course of treatment

Eventually, I decided if I went the chemo route and it didn’t work out, I would always regret not trying the transplant. And if I did the transplant and it didn’t work out, it would at least feel like I gave it my best shot, so I really committed to the transplant.

What triggered my release from the hospital was my immune system came back up. 4 weeks in, they did a bone marrow biopsy and they said there was no cancer. Huge achievement, but this is a cancer that always comes back so we’re on to the next step.

In a nutshell, they said, “We need to wait for the genetic and molecular analysis of your cancer, and that will put you in either a fairly favorable risk profile or an adverse risk profile. If it’s the former, you’ll probably get by with more chemo. If it’s the latter, you’ll probably need a stem cell transplant.” I thought, here’s a fork in the road. The decision will make itself.

When the results came back, they said, “You’re actually in an intermediate category. You’re not