Jason’s Stage 4 Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) Story

Jason W., Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL), Stage 4

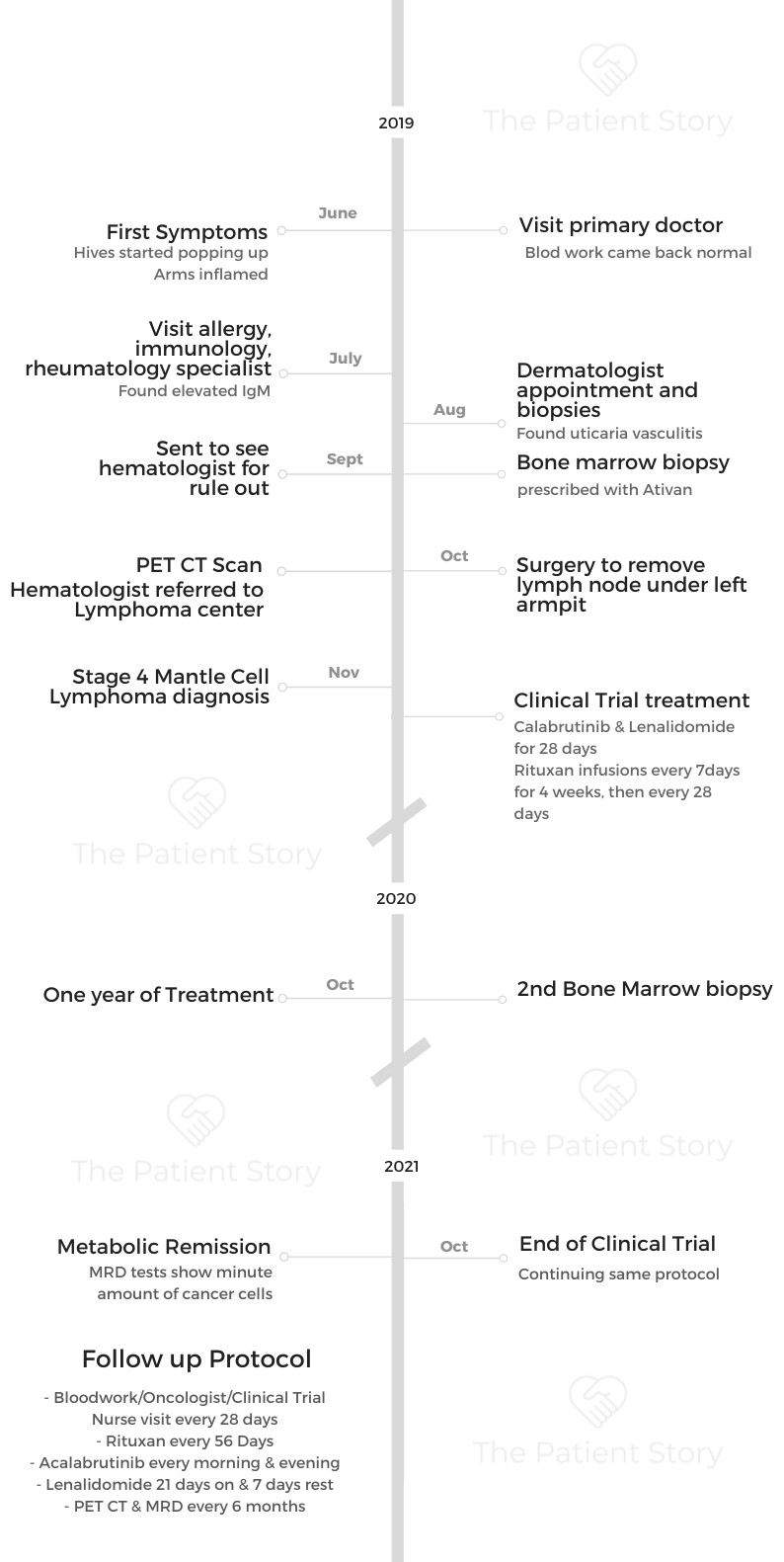

Symptoms: Hives, inflamed arms

Treatments: Calabrutinib, Lenalidomide, Rituxan

Jason’s Stage 4 Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) Story

Jason is a New York entrepreneur, tennis player, theater-goer and traveler who says he loves the lights of Las Vegas.

Things shifted in 2019 when Jason, at only 39 years old, was diagnosed with stage 4 mantle cell lymphoma, a rare blood cancer that is more common in men over 60 years old. His diagnosis almost turned his world upside down, and he was thankful he had become an entrepreneur prior to his own treatment.

In this video series, Jason shares his story of diagnosis, clinical trial, treatment and how cancer changed his life. His story is such an inspiring example of patient self-advocacy.

Thank you so much for sharing, Jason!

- Name: Jason W.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- 1st Diagnosis:

- Age at DX: 39 years old

- Symptoms

- Hives

- Tests for DX:

- Bone marrow biopsy

- PET-CT

- Treatment:

- Acalabrutinib

- Lenalidomide

- Rituxan

- VIDEO: The Mantle Cell Lymphoma Diagnosis

- VIDEO: Treatment & Clinical Trial Experience

- VIDEO: Life After Cancer (Quality of Life)

- Mantle Cell Lymphoma Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

VIDEO: The Mantle Cell Lymphoma Diagnosis

His blood work and everything seemed normal. Except for the increasing itch and pain from hives and inflamed arms, Jason and his primary doctor thought it was nothing serious.

Specialists couldn’t find anything until he was referred to a hematologist. A bone marrow biopsy and PET CT later confirmed cancer. Jason was diagnosed with mantle cell lymphoma at a very early age of 39.

About me

I’m in New York City, and pre-cancer diagnosis, I was an entrepreneur. I guess I still am, and I have a small business. I’m a tennis player, a theater-goer. I like to travel. I like to gamble. I go to Las Vegas pretty regularly. I’m most passionate about my business, which is a production supply and walkie-talkie production services company in New York City and Greenpoint, Brooklyn, which is a great neighborhood in New York City.

I’ve been in video production services for over 20 years. In 2017, I started my own company after being a freelancer for many years. That was actually kind of a magical experience because if I didn’t start my company, I don’t know how I would have fared this storm.

If I was still in the freelance world, producing shoots or working for somebody 40 hours a week, I think that I would have some pretty significant challenges dealing with the cancer diagnosis and the treatment and the ongoing treatment. Being an entrepreneur has been very lucky and fortunate for me.

My first symptoms

It was about 2.5 years ago, the summer of 2019, and the very first symptom was on my arms. I was getting a rash. It was very red and bumpy and itchy. It started on my forearms, and I really didn’t think much of it for the first 2 or 3 weeks. I really didn’t think much of it at all.

I was out to dinner with a very close friend of mine, Adrian, who happens to be a doctor himself. He’s a hospitalist at Weill Cornell, and he’s a really great doctor and a really great friend of mine. We were meeting up for dinner, and he said, “What’s on your arms?” I said, “I don’t know,” and he’s like, “you should have it looked at.” I said, “Yeah, I don’t think it’s anything to worry about.”

Another couple of weeks went by, and it was still there. His comment was sort of in my head, so I made an appointment with my primary care physician. I’m probably going 5 weeks after the first sign. I go into the primary care office, and at this point, there’s hives on other places than my forearms.

Mantle cell lymphoma diagnosis

The primary care physician says, “It looks like hives to me. Hives are really common. We get a lot of people in here with hives, and we run all sorts of tests and are looking into it. Most of the time, they just go away, and we never really figured out what it was.”

We talked a lot about it, like “Did you change your detergent, or did you change your soap?” Then he took a lot of blood and ran my blood work.

He’s a wonderful doctor. I love my primary care doctor. I still have him today.

He called the next day. “We got your blood results back. Everything looks perfect. Hopefully, this just goes away.”

I said, “Oh, great, blood work came back great. Hopefully, this will just go away.”

Time went by, and it started getting worse. It started spreading to other parts of my body. It started becoming more itchy, more inflamed. It went from just being on my forearms to being all over my chest and all over my stomach and down my thighs. It just sort of progressed.

I went back to see him again. He said, “I’m not quite sure with your blood work being right what it could be. Why don’t we look into going to an allergist, immunologist, rheumatologist-type person and a dermatologist?”

I went to somebody who had a specialty in all of those categories —allergy, immunologist, rheumatologist. We ran blood work like I’ve never experienced. The number of vials of blood that I gave and the number of tests that I did over the course of 2 months with this person was just over the number. The bill was also over the top. The only thing that came back was an elevated IgM. That was it. That was the only thing that came back irregular in my blood work.

The dermatologist initially said, “I don’t think these are hives. I think it could be something else.” While everybody thought it was hives, he said, “There’s a chance it could be this. It’s a rare thing. Let’s biopsy a few in a couple of different places on your body.” He biopsied, I think, 4 areas.

We ran blood work like I’ve never experienced… The only thing that came back was an elevated IgM.

Describe the biopsy

It’s like a punch biopsy, where they basically think you have one hive that’s sticking up. They just take the whole thing and then send them to a lab.

They took 4 — took 2 off my back and 2 on my stomach, or something like that. Those came back as urticaria vasculitis, so that is hives. The vasculitis meant there were hives not only on top of my skin, which are traditional hives, but also under, in the derma.

I was getting hives basically on both sides of my skin, the exterior and the interior. We’re 4 or 5 months into this with me having hives, and they’re just progressively getting worse. There were some sleepless nights. It was unbearable not to itch them, and then it would create scabbing and blood. My sheets were tinted with blood spots.

It was painful. There were a few nights when the pain level was an 8 or 9. Looking back, I can’t believe I didn’t just go into the emergency room.

Looking back at what I was doing — laying in a bathtub and trying to throw ice all over me, doing all of these things to try and come at it — I should have just gone to the emergency room.

»MORE: Read in-depth patient stories and background on mantle cell lymphoma

This young girl comes in and tells me that we’re doing a bone marrow biopsy. She explained it to me, and I literally started crying.

Understanding pain tolerance level

The dermatologist gave me steroid cream, which was helpful. I put that all over, and it was really helpful.

As we were going through the diagnosis process, eventually I landed at a hematologist. The allergist-immunologist said, “I have to send you to a hematologist because you have an elevated IgM, but there’s nothing wrong with you. I assure you your blood work looks so great. But we have to do it. It’s called a rule out.”

I went to the hematologist, and I’m there for a rule out.

What’s a rule out? I don’t know what a rule out is. I went into the office, and they put me in a room. The PA (physician assistant) to the hematologist that I had an appointment with comes in and is very cheerful and says, “Do you know we’re doing a bone marrow biopsy today?

I was like, “What? What is that? I’m going in there for a rule out. I don’t even know what that word means.” Then this young girl comes in and tells me that we’re doing a bone marrow biopsy. She explained it to me, and I literally started crying.

What in the world is going on here? Then the doctor came in (the hematologist), and I’m crying, and she’s trying to talk me down. I said, “Look, you guys didn’t tell me that this is what’s happening. I could have mentally prepared for this. I could have brought my friend. I am not doing this today.”

How did the bone marrow biopsy feel?

For me, the gravity was maybe more extreme than most people.

I watched my mom die of cancer. She died when I was 19 years old. When I was in that room, I didn’t think I had cancer. I thought I was going to a hematologist for a rule out.

I’m sitting there crying and upset, thinking, “Is this person thinking that I have cancer? Now I have cancer?” This hematologist is saying, “This isn’t that.” That was what she kept repeating. “What your mom went through — this isn’t that.”

They hadn’t diagnosed me, and it was supposed to be a rule out. I don’t think at that point anybody thought I had cancer, and that’s what I found along the way.

It was like, “I’m sure you’re fine. Don’t worry about it for like 5 or 6 months.” But actually, there was something very big to worry about.

For me, the emotion that was coming from there was, “I’ve seen people battle cancer. I’ve seen people die from cancer.” My mom wasn’t the only family member that succumbed to the disease. I have many aunts and uncles that have passed away from cancer.

I was very close to my mom. I was young and in high school during all of her treatments, witnessing all that. That was in the 90s. A lot has changed between now and then. I have to say, it was probably a lot worse to have cancer in the 90s than it is in the 2020s, based on what I witnessed when I was a younger person.

At that moment, the tears and the emotion that were happening in that room were like, “I’m in a hematologist office with this person who thinks I have cancer because they want to do a bone marrow biopsy. Here begins the torture.”

I had always said after witnessing my mom go through all that that I would never do chemotherapy. After I saw that, I said, “I’m never doing that.”

I haven’t done traditional chemotherapy, and it was a big part of my decision-making. To avoid it was probably historical.

My mom battled breast cancer for a long time. She had the initial cancer reoccurrence twice. Then I think she was battling it for that third time, but it had spread to her sternum. Then, from there, it went up to her brain. That’s ultimately how she went from cancer.

Guidance on people on PET-CT scan

They had basically said, “Okay. When can you come back?” I said I’ll come back in one week, and they said, “Okay, well, we also want you to get a PET-CT.”

I don’t know anything about a PET-CT. I don’t know what it is. Nobody tells me. I go, and I’m by myself.

There’s a nurse, and he’s very nice. I’m asking a lot of questions. He’s got to put an IV in me. I’ve never had an IV before in my entire life. He was asking me if I’ve ever had this done before, and I said no. Then he starts explaining what he’s going to inject in me. I said, “Is this dangerous? This sounds dangerous. Is this bad for my health?” It’s not something you should do. It is radiation and radioactive material.

He said, “If your doctor has ordered the test, then it’s probably really important that you do it.”

I said, “Okay, that makes sense.” But I had no idea what was going into it.

There was a lot of that — the first time going to the doctor’s office, going to the infusion center, getting a PET scan and getting a bone marrow biopsy. It’s really scary that first time. The buildings look so different the first time I go from the second time I go.

The first time I go, I just have this scary memory of them. Then as I go back over and over again, it fades, and they seem like normal places to me. But I can always remember the first time I go to a building and get that first thing I’ve never done before. It’s just like a very sterile, scary kind of situation, but it seems to fade away after you do it the first time.

Describe the PET-CT scan

They set the IV and inject you with something that I still don’t 100% understand.

I’ve asked a lot of questions about it, but it’s like I get a piece of paper here in New York City that I have to carry around with me because they have monitors in the subways looking for dirty bombs, like radiation bombs. If you get a PET-CT, there’s a chance you can set one of those off, so I get a piece of paper walking around New York City.

They tell you don’t hug children for the first few hours when you’re done with it and drink a ton of water. You sit there for an hour in an isolated room. From the looks of it, the room is meant to keep whatever you’re radiating from your body from other people.

It’s a very lonely hour. You’re not allowed to bring a friend because you’re emitting something. When they’re guiding you in, they almost put some space in between them and you. Nobody’s getting close to you during that process and for a little bit after. Then, after the hour, they call you in.

They also will have you drink a substance while you’re waiting. I can’t remember what it is exactly. It starts with a G, but it’s basically sugar water.

It’s a very lonely hour. You’re not allowed to bring a friend because you’re emitting something. When they’re guiding you in, they almost put some space in between them and you.

You’re getting the injection of something going into your veins that helps them see imaging of your organs and lymph nodes. Then you’re drinking something that’s probably insulin or glucose-type base that’s going throughout your whole body. That’s sort of the magic for making the imaging.

You do that for an hour. You sit there, get an injected, drink all the juice. Then they bring you in, and you go lay down on a long, little table. Then they send you through a tube.

For me, because I’m stage 4, my lymph nodes are from my groin to neck. My scan probably takes longer than most people’s, depending on the type of cancer you have. For me, they start on my thighs, and then they go up to my ears. It probably takes about 28 minutes to do that scan.

You just sit there and don’t move for 28 minutes. Then they let you go with your piece of paper to get out of jail if you set off a New York City MTA radiation monitor.

Dealing with scanxiety

It’s not just about scans. It’s just that waiting period, essentially for any results or even before the procedure.

I’m not a fan of bone marrow biopsies. I don’t like them, and I will definitely be kicking and screaming if I have ever to do another one. We’ll need to work on some other ways of either medicating me more or making the experience better for me, because I don’t know if people know exactly what it is.

Still, they’re essentially taking a very long needle and jamming it into your lower back and going straight into the bone to the core of it and removing some marrow. At the same time, going back in where they went in and taking what’s called an aspiration, which is a small amount or a tiny piece of the bone as well. Sometimes they’ll even get marrow from 2 different spots.

I can’t imagine anybody would want to do that. I don’t like the experience at all. I’ve done 2 of them. I’ve done the Ativan (lorazepam) stuff. It wasn’t enough for me.

I always say I’m done collecting bad memories of bone marrow biopsies. If they want to do another one, we’re going to have to work something out. I don’t want to do it under the circumstances I’ve done the last 2.

I had a long wait to get into actually meeting my oncologists who I have now.

The hematologist who did the bone marrow biopsy — the first one who was doing the rule out with the PET scan — had sent my bone marrow out to the lab to see what it was. Before it went out, she said she took a smear of it, put it on a slide and looked at it under a microscope.

She said, “I can tell for sure you have B-cell cancer just by looking at it. I’m a myeloma doctor. I’m referring you to the Lymphoma Center. The bone marrow from the biopsy is being sent out to the lab. Your PET scans are still going through, but you need to call the Lymphoma Center. I referred you to somebody because I don’t do that. I do myeloma.”

Hearing and processing the news of cancer

It was literally on the phone with a doctor. I didn’t have a relationship with the same one who said, “This isn’t that.” It was a hematologist that I was sent to do a rule out.

It all happened very fast, and it was very shocking. I had no idea, and I would have never guessed that I had cancer.

It was hard doing the rule out. I thought I had to do all these horrible things just to appease the rule out. I was still in the belief that all these other doctors telling me, “Look, your blood work’s perfect. I’m sure you’re fine.” I had so many doctors tell me that, from the dermatologist to the immunologist allergist, my primary care.

So many people were like, “I’m sure it’s probably just something immune, autoimmune.” In my mind, I just think, “Oh my God, I have to do these 2 horrible tests to help figure this out, but I do not think I have cancer.” That wasn’t what I was thinking at all.

When she said it, it couldn’t have been more of a shock. I was completely in shock. There wasn’t a lot of conversation. After that, it was just 1 or 2 questions. Her responses were like, “I’m not a lymphoma doctor. You have to call the Lymphoma Center.”

I got information that I had cancer, but then I didn’t really have anybody to ask follow-up questions. There’s a lot of B-cell cancers.

My friend who was a doctor, I called him. He’s such a great friend. He came over immediately within an hour, and we were able to talk, like, “Well, there’s some ones that aren’t that bad.”

We were going through the list. He was trying to talk me down a little bit. When I called the Lymphoma Center, they said, “We’re not seeing you until you have a lymph node removed. We’re going to need one in order to diagnose this formally.”

That period was 4.5 to 5 weeks from, “You have cancer,” to “What is this?” I had to find a surgeon, schedule an appointment with a surgeon to meet before surgery, then schedule a surgery. Then it goes out to a lab. They couldn’t have told me more times, “It literally takes a week. It takes 5 full days. It’s not going to come back any sooner. We assure you, 5 days is the earliest.” Then from there, then I have to get an appointment with the doctor to get the results.

It was a good 4.5 to 5 weeks of just complete anxiety. Those were definitely the worst weeks. The not knowing what my outlook is, what my prognosis is, what is going to happen in terms of treatment. Those were the worst.

The terrible part of it was the anxiety part that you sort of hinted at it when you’re waiting to get the scan results. That’s what made it so terrible.

The meeting with the surgeon and the appointments — all of that wasn’t a bad experience. I felt like I navigated it as fast as I could within the system. You call to make a prelim appointment with a surgeon on a Monday, and you get in on the next available — might be Thursday. You meet Thursday.

Then you got to get on the surgery calendar, which could be 1 day or 2 days a week because they’re meeting with so many people for pre-op and post-op. The surgeon just might schedule surgeries 1 day a week or 2 days max.

I understand the idea of just checking to the emergency room, but how much faster could it have been? I don’t know if that would set it up for me.

Describe the moment you got the results

The worst day was getting a phone call from the hematologist saying, “You have some B-cell cancer. I don’t know what it is.”

That was the worst day. I was crying and thinking, ‘This is it.’

Going in to get the formal diagnosis and meeting my doctor for the first time was a very long visit. I brought 2 friends with me. One of them was the doctor, which I’m very grateful for. We were there for a good 3 hours, and I had a ton of questions, collected over the 3 or 4 weeks that I was waiting.

My doctor, who’s at Weill Cornell, Dr. (Jia) Ruan said, “You have mantle cell lymphoma.” She explained it, and I immediately felt very lucky because the hematologist had referred me to the Lymphoma Center at Weill Cornell, and there’s a handful of doctors there.

The one that I just randomly ended up being assigned to happens to be the one specializing in mantle cell lymphoma. That was like a miracle in a way, because of the options there. I didn’t really pick. They just referred me to somebody. I just accepted the referral. That seemed magical. I got the exact right doctor that I should be seeing.

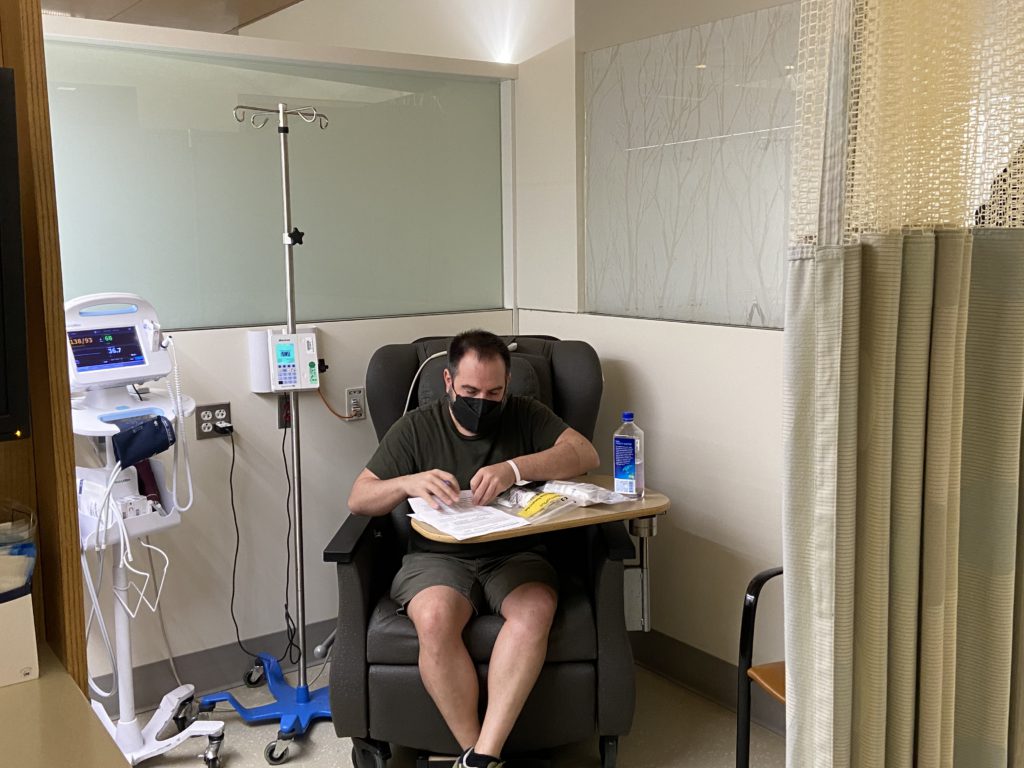

VIDEO: Treatment & Clinical Trial Experience

Jason used to be afraid of needles and procedures. Watching his mom go through breast cancer treatment through chemo, he was determined to try a different course of treatment.

Luckily, Jason got into a clinical trial introduced to him by his oncologist that turned out to be effective for him.

Treatment decision

My doctor said the traditional path to treat mantle cell lymphoma would include R-CHOP chemotherapy and then, depending on the result, could potentially be followed with a stem cell transplant. She said that she had another option for me, which was a clinical trial that she happened to be heading up for mantle cell lymphoma.

This felt very magical to me. I landed with this doctor who specializes in it, and now she’s also heading up a Phase 2 clinical trial.

She had presented both options. I knew instantly I wasn’t going to do the R-CHOP chemotherapy, because I told you I wasn’t going to do what I saw my mom did at that moment.

My friend who was a doctor was there with me. We asked a lot of questions. He asked a lot of questions as well about the clinical trial. She left the room, and I turned to him and said, “What do you think?” I just wanted his opinion. But in my mind, I already knew I was not doing that R-CHOP stuff.

He said, “I think you should do the traditional route. There’s just more data. They’ve been using it more. We know it works.”

I said, “I think I’m going to go the other way.”

She came back in, and I asked a lot more questions. They presented me with a stack of papers, like a contract. I read through it all.

I sat there for like another hour, just contemplating which one to do. Then before I left, I signed all the paperwork for the clinical trial. She said, “All right, come back in a week from today, and you start.”

So that’s how I started.

Describe the cycles

For the first 4 weeks, you get Rituxan every week, and then after those first 4 weeks, you will get it every 56 days after that. The other 2 medications are both oral, but the Rituxan is infused. You go to the hospital, to an infusion center, and do that.

The first 4 weeks were back to back, 4 weeks in a row. Ever since then, I just go in every 56 days. I take acalabrutinib every morning and every night, every single day, and I have for over 2 years now.

For the lenalidomide, I take it like birth control. 21 days on, 7 days rest. I’ve been doing that for over 2 years now as well. The first year, I took 20 milligrams of lenalidomide, and then for the second year, they let me reduce the dose to 15 milligrams. Basically a 25% reduction of that drug to give a little break and hopefully reduce the side effects by 25%.

Describe the difference in side effects

It’s so hard to measure them. But I do remember that the first year was way harder.

I remember in the beginning — the first 6 months — were way harder, and I don’t know if that’s you just get used to it, or your body gets used to it, or you adapt. I do remember that the side effects were worse in the beginning, and maybe it has to do with just managing it better now.

I can tell you that acalabrutinib causes headaches for me personally. It just straight up causes headaches. They resolve from caffeine; if you get a headache and drink a coffee or take an Excedrin that has caffeine in it, it’s pretty quick. It goes away.

Dr. Ron, who’s been at Phase 2 clinical trial, it was her tip on that, and it worked. If I ever got a headache, sometimes I’d wake up in the morning and just be like, “Oh, my head is killing me.” One cup of coffee, and it would start to fizzle out.

Luckily, I like coffee. I drink black coffee every morning. If I didn’t drink coffee and had to take Excedrin every day, I might feel differently about that.

How long would the coffee last in terms of helping?

I was a 3-cups-of-coffee drinker every morning to begin with before all of this. The headache is every day, but it subsides every single day from caffeine. Normally, if I wake up in the morning with the headache and drink, it goes away.

I normally don’t get a headache, maybe not get one for the rest of the day. If I get one in the afternoon or evening, I can pop an Excedrin; it’s not every day that you get a second round of headaches. It seems like waking up with a headache, as was my experience.

Any other side effects that were really tough?

It’s hard to tell which ones are doing which ones, so these are just my opinions.

I really think Excalibur is causing the headaches. Then with lenalidomide, I feel like it causes a ton of fatigue.

The pills are causing all my fatigue. That’s my number 1 side effect. That’s my biggest problem. It’s like tired, but fatigued isn’t tired, and I want to say weak, and fatigue isn’t weak. It’s like putting those 2 in a blender, and it’s something else let a little light that hits me pretty hard.

If I go to work and I’m moderately active throughout the day, I’ll come home, and that’s it for the day. I’ll be on YouTube in bed for the rest of the evening.

Fatigue is the biggest side effect of lenalidomide.

What does a normal day and fatigue look like?

Even when I was having symptoms with those hives, I was out to dinner. I was meeting friends.

I don’t do that anymore. If I do a workday, that’s it for me. I don’t have anything after work. There is nothing left for me to give.

I had a doctor’s appointment at 2 o’clock yesterday, and the thought of having to get up and go into Manhattan and come back, the level of exhaustion is just like, “I don’t want to do that.”

For people who’ve never been on treatment or cancer or if you’ve ever been so tired where you don’t want to take public transportation, and you just pay for that car, that lift — that’s fatigue.

I can’t deal with getting on a train right now. I can’t deal with getting on a bus right now. I’m so lethargic. I’m paying for a Lyft or an Uber. Maybe that’s a New York City analogy, but that’s how I feel about a lot of things.

Like walking the dog. I just don’t want to do it. I used to play tennis. I used to go meet up with friends all the time after work. I don’t meet up with anybody after work. I don’t play tennis anymore.

The amount of hours I have to dedicate to the day is a lot less. I’m not what I used to be during those hours.

What helped you through the fatigue?

I’m still working on it. I met with an integrative health doctor yesterday. We talked, and the soup of the day was fatigue.

This doctor is at Weill Cornell, a real doctor, a board-certified doctor. We were talking about solutions for it, and one of the things we talked about was potentially doing some weight training and some cardio, even though that sounds totally counterproductive and the exact opposite of what you would want to do if you’re so tired.

We talked about strengthening, building muscle mass and strengthening the heart to potentially alleviate the fatigue a little bit or improve my quality of life. It’s a long process. We talked about starting really small and building up to maybe 150 minutes a week combination, maybe like 5 days a week. Then maybe year 2, punching up to 300 minutes, but in very small increments.

That may be a solution. I’m going to try, but it’s not like, “Boom, that’s fixed.” It’s going to be a path and a journey. I have to do the work to have a little bit better quality of life hopefully. Because for me, my protocol is I’m going to keep doing this therapy for as long as it continues to manage my disease or until I can’t handle it anymore.

Investing in this idea may be worthwhile for me, considering I’m going to keep taking these medications.

What’s the follow-up procedure for monitoring MCL?

I’m incredibly fortunate because the clinical trial was trying to get FDA approval, and there are people that are analyzing data, and there’s research.

I received MRD tests regularly during the clinical trial for the formal 2 years. I got one before I even started and then at different intervals throughout the trial.

From what I understand, even though they aren’t FDA approved for mantle cell lymphoma, the researchers can identify if there are any cancer cells in my blood down to 1 in 2 million or something like that. From what I understand, it’s a very sophisticated science and test.

We know from my last test 3 months ago that there’s still a minimum amount of cancer cells in my blood. But if I wasn’t getting the MRD test and I was just getting R-CHOP or whatever and not on this clinical trial, they’ll just send me to get a PET scan, and they would tell me that I’m in remission. That’s what my doctor said.

She goes, “I can’t say that to you because I have this other test over here that tells me the truth, in a way.” She said, “Let’s call it metabolic remission.”

All of my lymph nodes are now the same. They’ve shrunk down to a size that fits into the normal zone. None of them are like lighting up like a Christmas tree as they used to. From a PET scan point of view, I look good. But from the MRD test, we know that it’s still present.

Again, they use the word “minute.”