Paul’s Prostate Cancer Story

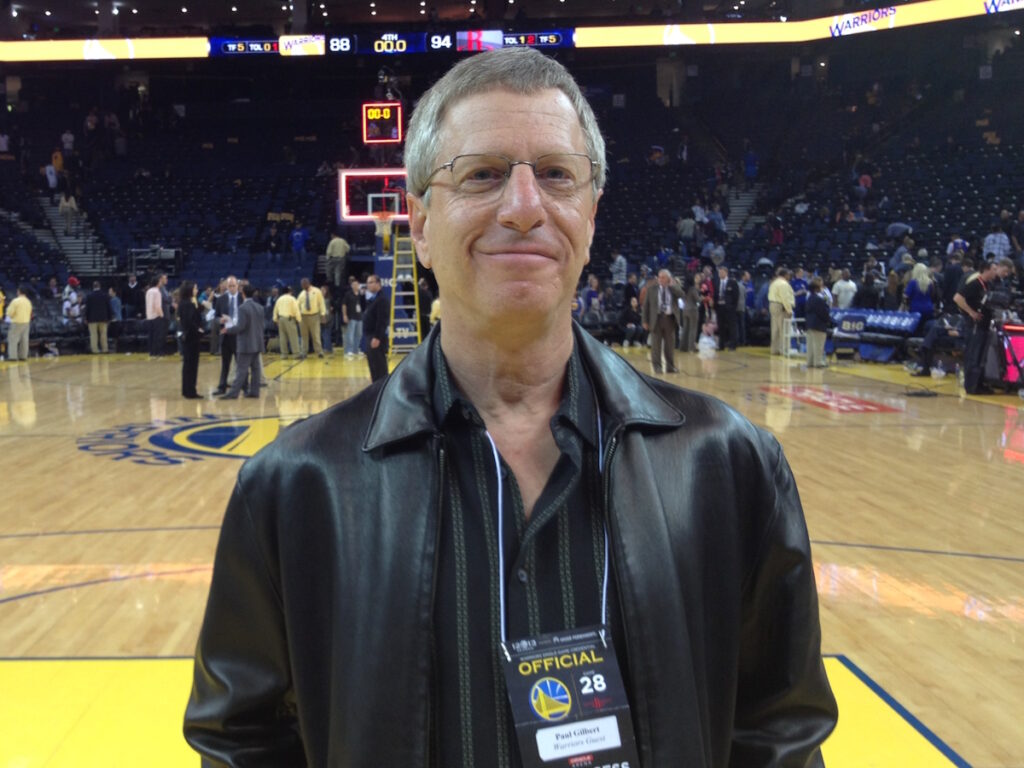

Paul G., Prostate Cancer, Gleason 7

Symptom: None; elevated PSA levels

Treatments: Prostatectomy (surgery), radiation, hormone therapy

Paul’s Prostate Cancer Story

Interviewed by: Stephanie Chuang

Edited by: Bella Martinez & Katrina Villareal

In 2019, Paul received a shocking diagnosis of prostate cancer after a routine check-up uncovered a Gleason score of 4+3. Reeling from the news, he underwent radical prostatectomy surgery.

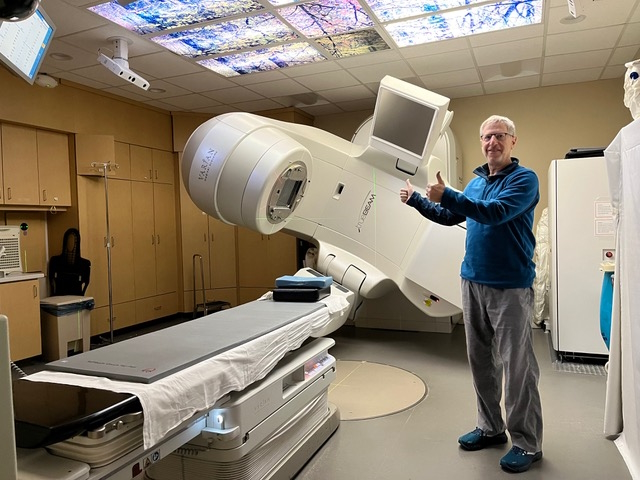

After connecting with a prostate cancer support group, Paul was able to make sense of treatment options and find emotional support. But two years later, a follow-up PSA test revealed rising levels, indicating his prostate cancer had returned. This relapse encouraged Paul to research integrative medicine techniques and shift his mindset with mindfulness practices as active parts of his healing journey.

Now in remission following radiation and hormone therapy, Paul took to writing for Medium where he shared his cancer journey and the lessons he learned along the way. He now shares his story with us and discusses how changing his mindset and focusing on positivity has helped him on his healing journey.

Paul’s story is part of the “Our Voices, Our Power” series by The Patient Story. Discover more of the series by exploring Tim’s stage 1 prostate cancer story.

Thank you to Janssen for its support of our patient education program! The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction

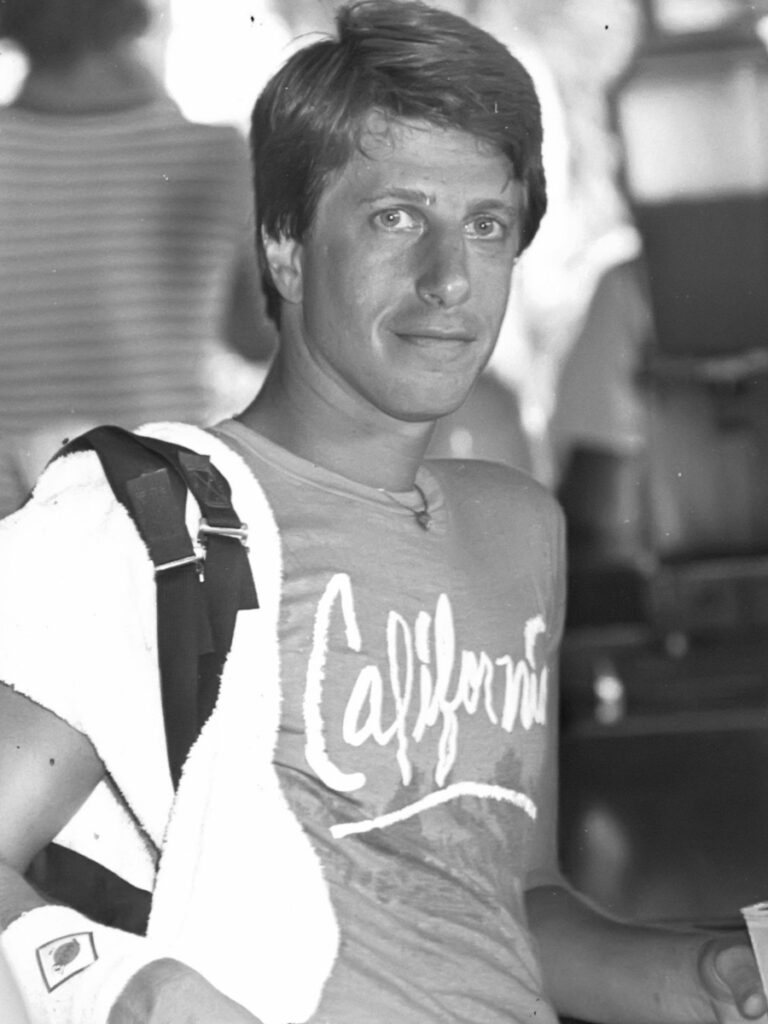

I grew up outside New York City, in suburban New Jersey. I was an athlete and an editor of my school paper.

I decided I wanted to go to college in California, so I went to UC Santa Cruz, 2,000 acres of rolling meadows and redwoods overlooking Monterey Bay. I invented my own major called The Politics of Mass Media. I was a disc jockey and had a sports show on the radio station.

After graduating, I realized there were no media jobs in Santa Cruz, so I went back to New York City to start my career.

I was highly motivated. This was the 70s, so there were plenty of other highs as well. I wanted to explore different things. I knew what I liked. I loved sports and I liked writing.

Being a Storyteller

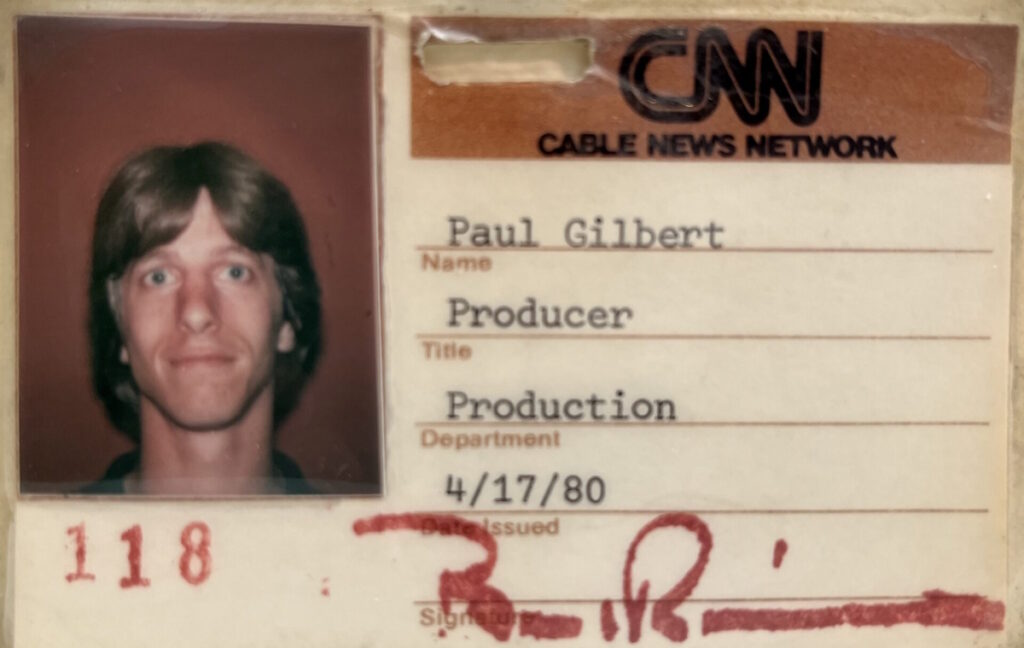

I jumped from the radio to CNN when it was first starting. I went down to Atlanta where it was going to be the first 24/7 station. I was hired as a writer. Within a week, I became a producer and a producer anchor within two weeks. At the time, that was the way CNN was because they didn’t have enough people.

I learned to become a storyteller in the video medium. I ended up doing high-end corporate videos and nonprofit videos, so I had to learn how to tell those stories as well.

After 40-plus years of being in media, I consider myself — and I say this with humility — a master storyteller. I’m still working on my craft.

I was probably telling stories when I was a child, too.

The great gift is not only being loved but giving love.

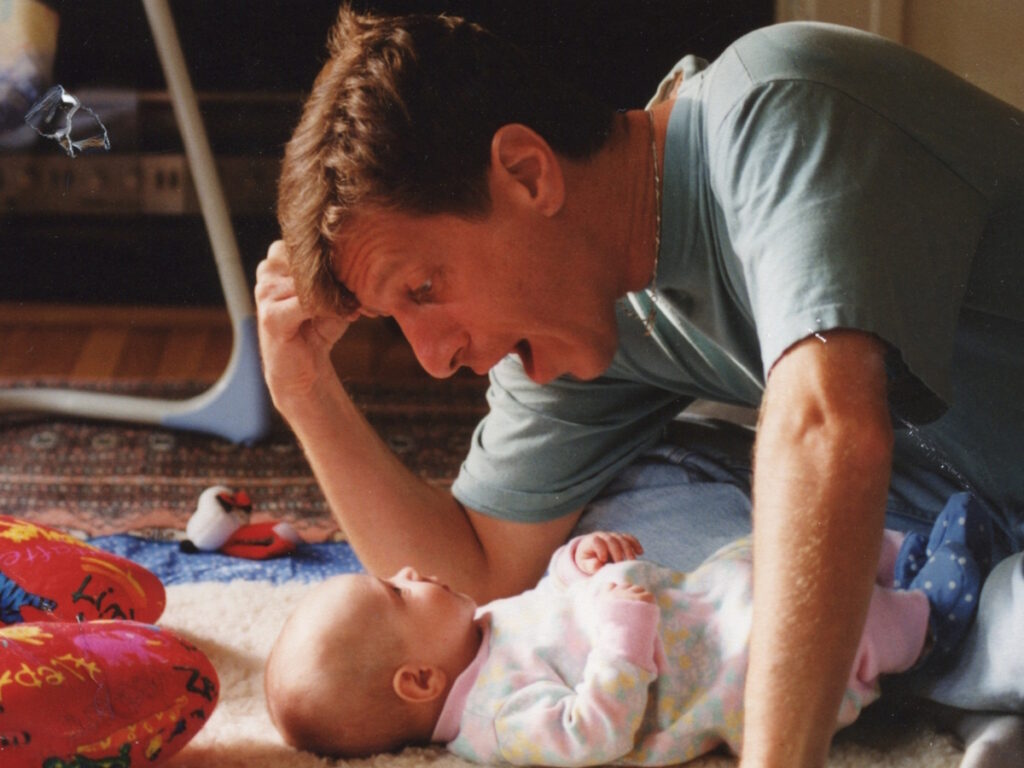

Meeting My Wife

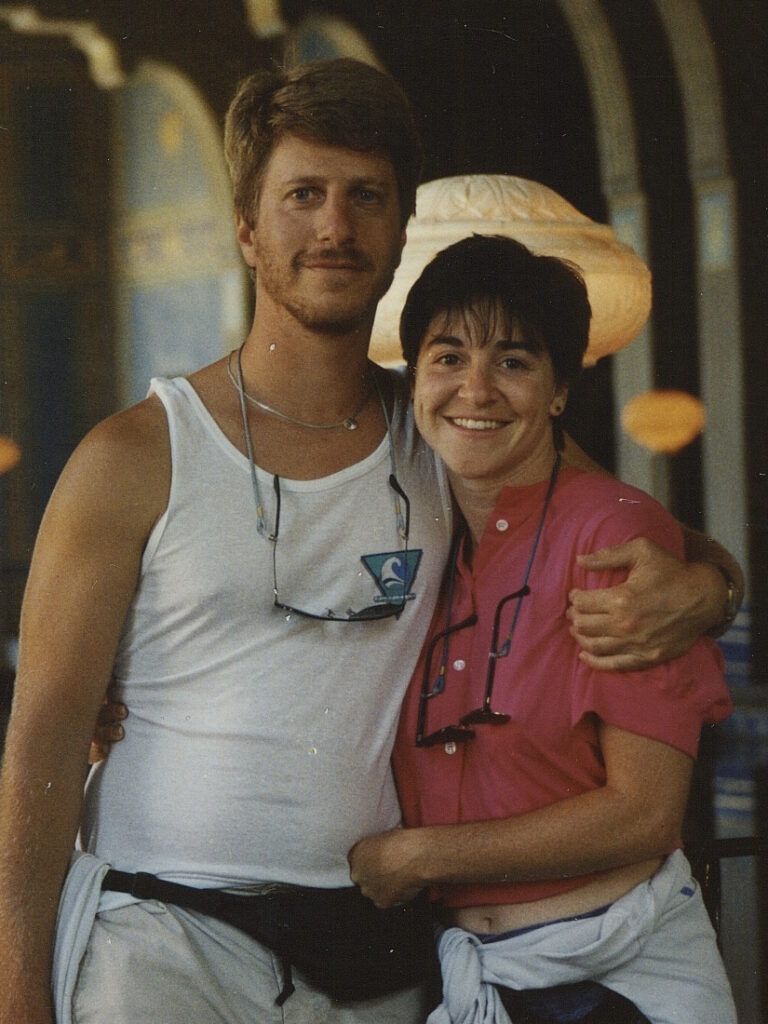

In 1988, I was in Central Park riding my bike approaching Strawberry Fields at 72nd Street. I saw this young woman, Wendi Messing, lacing up her roller skates and when she got up, I sidled up next to her and said, “Are you going to Disco Heaven?” This was a place near the volleyball courts where everybody skated around with giant boom boxes. She’d never been there before. It wasn’t a truth or dare moment, but I pushed her a little bit, so she went up there and skated around having a grand old time.

I was riding my bike around, but I was watching. When she left, I rode behind her and threw out a line. She bit and I reeled her in.

We sat and talked. She was an advertising producer. We were both cutting videos to the song Hot Together by the Pointer Sisters. Talk about serendipity!

We made a date to get together. As the months went on, the other thing we found out was we didn’t want to live in New York anymore. We ended up in San Francisco and started from there.

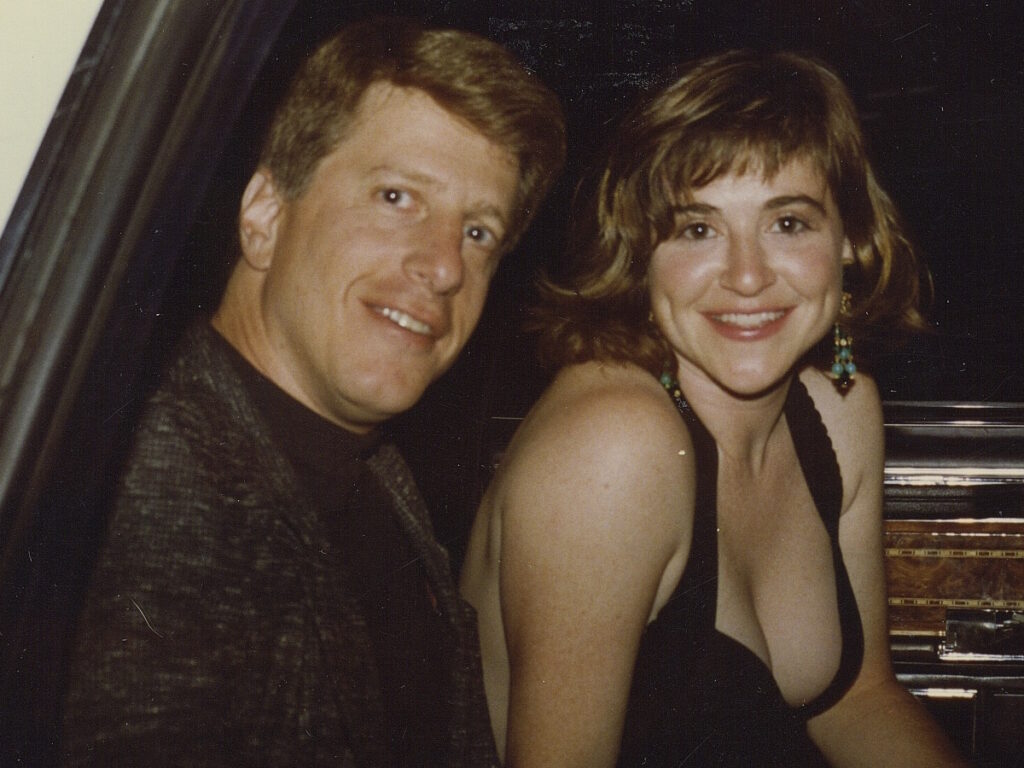

I had been a serial dater. I was in my mid-30s at that point. They said she was the kind of girl I wanted to marry. She was hard-oriented, sweet, and really cute. We were in the same business. We were both Jewish. A lot of things lined up.

The great gift is not only being loved but also giving love. I think in some ways, we want that even more. I feel that with my dog. As much as they say, “Dogs give unconditional love,” we also give them unconditional love back.

I won’t use the word “caretakers.” We’re givers. I tell Wendi, “I never come home without something for you.” I’m always thinking, What could I bring her? I know she was always looking out for me.

When I was diagnosed with prostate cancer, I realized that I had gone from living a normal life to now all of a sudden, I’m in a club I never wanted to be a member of.

I realized that I had gone from living a normal life to now all of a sudden, I’m in a club I never wanted to be a member of.

Pre-diagnosis

Initial Symptoms

I went to a regular checkup and during the rectal examination, the doctor said he felt something. I didn’t know what to think. I didn’t think it was good, but I didn’t think it was terrible. He sent me to a urologist and said, “I feel something there. Let’s do a biopsy.”

I started to worry a little bit. Biopsies are not fun. They’re very invasive. They go in through your urethra and take samples. I was really sore afterward.

Diagnosis

Getting the Official Diagnosis

About a week later, I was in my car after a workout. I got a phone call from the urologist and he said, “You have prostate cancer.” That’s the minute your life switches.

Reaction to the Diagnosis

I was in shock. I was 63 years old, super healthy, and ate relatively well. I have a sweet tooth, but I didn’t have a lot of high-risk factors. There wasn’t a lot of cancer in my family.

Later on, I found out that two of my uncles had prostate cancer. It was like a kick in the balls, no pun intended. I was stunned. When I told Wendi, I knew immediately that she would be there for me 100%.

I had gone from living a normal life to all of a sudden being in a club I never wanted to be a member of. I’m young, I’m healthy, I eat well, and I exercise. How is this happening? It doesn’t sink in right away. You know that life will never be the same again.

I figured that, for now, I’m going to keep this to myself.

Choosing Who to Share a Cancer Diagnosis With

I’m a very private person. I have a few really good friends that I will tell almost anything, including women, friends, and couples. Unfortunately, both my parents had passed by then. Actually, that was probably fortunate because I know they would have worried so much.

My older brother had frontal temporal dementia and had passed, so it was only my younger brother who knew. I didn’t want to go through it with Wendi’s family. My thing is once you tell everyone, it’s out. You can always decide later on who you want to share it with and how.

I remember reading an article in The New York Times that said the way people react to news about cancer can be very draining for the person who’s sharing the news. They may ask a lot of questions, including a lot that you don’t know the answer to. They may offer advice that you really don’t want to hear.

Everybody knows somebody other than their family or friends who’s had cancer, but if someone’s had breast cancer, leukemia, or lung cancer, it doesn’t relate to prostate cancer. Sometimes people say things that are inappropriate and I didn’t want to go through that.

I figured that, for now, I’m going to keep this to myself because my Gleason score was 4+3. That’s a whole thing in itself. You start learning all these numbers — Gleason scores, quadrants of your prostate capsule, different kinds of reports, and genomic tests. It’s overwhelming.

They couldn’t find anything. That was encouraging… On the other hand, if you don’t know where it is, how are we going to treat it?

What the Numbers Meant

One of the first things I heard was that prostate cancer is a “good cancer.” I would never put those two words together. The reason they call it a good cancer is because it’s very treatable if it’s caught early. Not necessarily cured, but very treatable.

I didn’t feel like I was one of the lucky ones. I got prostate cancer. The word cancer is what you hear. I found that it gets very matter-of-fact with doctors. They’re compassionate, but their job is to tell you the facts and the statistics.

We were getting all these numbers, the Gleason scores, and I was a 4+3. There’s low risk, medium risk, and high risk. I fell right on the cusp of intermediate, but I was on the wrong side of it. 3+4 and below are considered good candidates for active surveillance where you’re watching your PSA levels. That made it a little challenging, too, because I wasn’t high-risk. I was on the cusp. But then they told me the genomic tests showed that it was aggressive, so that put me in another category.

PSMA PET Scan

I had a PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) PET scan, which is a highly sophisticated PET scan. They shoot you with radioactive isotopes and iodine. They couldn’t find anything. That was encouraging because it meant things were small and they hadn’t moved into my organs or bones. On the other hand, if you don’t know where it is, how are we going to treat it?

I didn’t want to share other than with Wendi. That’s how scared I was.

Breaking the News to the Family

I was somewhat obsessed with thinking about it. It was always in the back of my mind. It’s hard to avoid that when you have cancer.

I told our children a month or two after I found out. I didn’t want to worry them. As I was approaching surgery, I knew that I needed to tell them what was going on.

I also wrote an email to Wendi’s family telling them what was going on. I was going to have surgery, but I was very clear about my boundaries and that I didn’t want to discuss it.

At some point, I would share information as it came up. I might have gone overboard with this, but I was very firm about my boundaries. I know they care and they love me and want to support me, but I didn’t want to go down that road of getting lots of questions and phone calls, so I played it pretty close to the vest.

Processing the Emotions of Having a Cancer Diagnosis

When you hear you have prostate cancer, there’s a lot of fear because it’s a sexually related thing. You’re talking about your internal plumbing and the unknown side effects, which can be incontinence or sexual dysfunction. You don’t want to talk about those things. You also think about dying.

I didn’t want to put that burden of fear on other people. If I couldn’t project overwhelming confidence that I got this, I didn’t want to share it other than with Wendi. That’s how scared I was. I like to be in control as much as possible.

I also grew up in a household where there was a lot of emotional chaos. I’m sure that made me even more of a person who wanted to have control. Suddenly, I was thrust into this situation where I felt like I had no control. I did share it once I knew I was having surgery.

I was tortured during that time by not wanting to make the wrong decision.

Treatment

Treatment Options

I had one of the top surgeons in the country, so I was confident that I was in good hands, but you have to make a decision early on.

Are you going to do radiation or are you going to do surgery? The catch-22 is if you choose radiation, you can’t do surgery later on. If you choose surgery, you can do radiation later on.

I’m in limbo. We can’t find it, I’m on the intermediate to low risk but on the wrong side of it and it’s aggressive.

I wanted more opinions. I didn’t want just a second opinion, I wanted a third opinion. The doctors kept saying, “We think it’s confined to the capsule based on what your Gleason score is and your PSA levels,” but they couldn’t guarantee it.

My initial diagnosis was in January. Over the next months, I was tortured not wanting to make the wrong decision. I had the surgery in April.

Surgery

One of the big concerns of surgery is nerve sparing because there are all these delicate nerves around the prostate. You’re anesthetized and you know that this robot is being controlled by a surgeon. I came out of surgery very groggy. The surgeon said, “I was able to spare your nerves and didn’t see anything outside the capsule.” I felt like that was good, but I was also wounded to the core.

The surgery was a traumatic shock to my system. It was good that it was confined to the capsule. It gave me some relief. Having a catheter is weird. You walk around with this bag.

For someone who liked to be in control and make things happen, it felt like things were happening to me and they were out of my control. That’s a tough one to crack.

Support

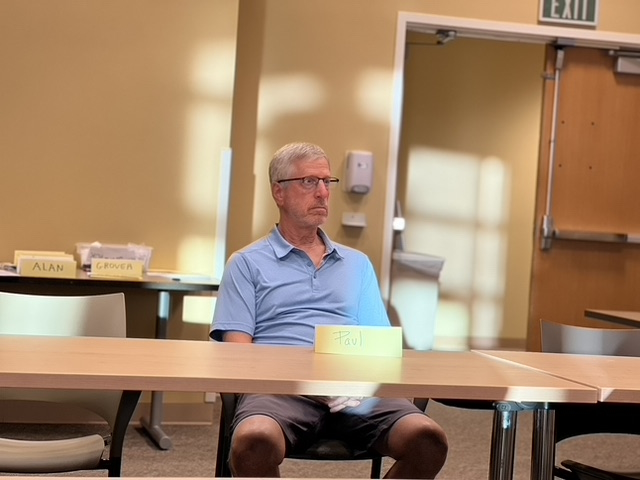

Finding a Cancer Community

I joined the prostate cancer support group at MarinHealth. They offer so much information. It’s the guys who’ve been in the trenches. I don’t want to say they knew more than my doctors, but they’d all been to so many doctors. Some had surgery, some had radiation, and some were on active surveillance. They knew all the drugs.

I was 63. I never thought of myself as old. I thought of myself as young. Part of me still feels 18 or 25. You get a cancer diagnosis and a prostatectomy and you start to feel a little old fast because you’re wounded. There’s no certainty that you’re ever going to be whole again.

You wonder if you’re ever going to get your old life back. For someone who liked to be in control and make things happen, it felt like things were happening to me and they were out of my control. That’s a tough one to crack.

When you get a cancer diagnosis, you’re a member of a club. One thing that’s really positive about that is every man that I met who has gone through this wanted to support me. They’d call and say, “I’ll be happy to talk to you about it.” A lot of them say, “You’re going to get through this. It’s going to be okay.”

They talk about what happened after surgery, incontinence, drugs, shots, pumps, and all the sexual things that you think, I don’t even want to know about, but you do want to know about it. I felt like I was in a community, but at the same time, it was a community club I didn’t want to be in.

It was not pleasant to have to discuss the fact that my body had felt like it betrayed me.

Once you’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer, all of a sudden this community opens up to other men who’ve gone through this and they all want to pay it forward. They all want to tell you about their experience and support you through yours to reduce the worry and to give you information you may not get from your doctors. There’s so much information from doctors that it’s overwhelming. To have more practical terms broken down step by step makes a huge difference.

When you’re one of the new guys in the cancer support group, you can feel the fear in the room. There’s a separation between people who’ve just found out who sometimes bring their wives with them, people who are trying to make a decision on how to be treated, and men who’ve been there and keep showing up over and over again to support you.

It was not pleasant to have to discuss the fact that my body had felt like it betrayed me. That was not an easy thing to talk about. I tried to be matter-of-fact about it, but I was definitely under a lot of pressure and stress.

These were now my people. It was healing in one sense, especially all the information they had that was easy to understand. But sometimes, there were people in there who were terrified. I had a hard time being around that energy.

As I went to more groups and more sessions, I realized it’s geared toward men who are just finding out they have prostate cancer. There’s a lot of that initial overwhelm.

Your doctors are great, but the support group provides things that the doctors don’t.

The Power of Having a Cancer Support Group

It was a safe space to talk because everybody in that room either has it or had it. It is important to unburden yourself however much you’re comfortable doing. The unspoken question for everybody is: how is this going to affect me as a man? That’s what people want to know. The cancer support group provides a place to share however much you want to share and ask any question you want to ask.

You’ll find out that your doctors are great, but the support group provides things that the doctors don’t. It provides emotional support. My doctors are compassionate, but it’s not their job to hold your hand. It’s their job to take care of you medically and to give you the facts.

Sometimes the facts are pretty scary — the percentages of survival, the percentages of when the disease could come back. I encourage men to go to prostate cancer support groups and decide for themselves. Is this for me? How much do I want to share? Are there men I want to stay in touch with during this or afterward? There are a lot of men who come there.

If they’re not done with prostate cancer, they’ve been dealing with it for a long time. They’ll tell you almost anything you want to know. It’s a chance to be around experienced veterans. You can always call someone outside of the meetings. I called the person who leads our group, Stan Rosenfeld, my prostate cancer rabbi because I could call him anytime. There wasn’t anything I couldn’t ask.

Having Someone to Answer Your Cancer Questions

It took some of the angst out of it. It made it accessible. The information was accessible whether or not I liked hearing it. Cancer is not fun. You’re not at a men’s group to talk about work and family. You’re dealing with your mortality, but there’s no other space quite like it. You’re amongst your peers and they’re going through the same thing you are.

I didn’t get into saying I’m really scared. You don’t hear me say things like that, but you can feel it. I’m sure they can feel it. The sense of empathy and caring and wanting to make men feel informed, that’s part of being a little bit more in control if you really understand your options.

They know we’re scared. I didn’t feel the need to say, ‘I’m really, really scared.’

Not Discussing Feeling Afraid

It’s not my nature. I’m not going to say I’m scared shitless. I’m afraid I’m going to die. I have no control over this and my life will never be the same. That’s not what I wanted to share with them.

I wanted them to give me some information and hear some solutions. Sometimes that’s what we’re looking for, solutions. You have a big problem and sometimes there aren’t solutions other than looking for second opinions and third opinions. Facts are facts. You’ve got prostate cancer, this is your Gleason score, and you have to deal with that.

It’s a foreign experience to be in a group. All of a sudden, you found out you had prostate cancer and you’re in a group of 20 men who also either had or have prostate cancer.

Oncologists use the term “no current evidence of disease,” but they never use the word “cure.” It’s really strange at first to be in this room with all these other people going through the same crisis. They know we’re scared. I didn’t feel the need to say, “I’m really, really scared.”